The Privilege that Defines Millennials, Managing Gen Z and When are Humans at their Happiest?

Hope you're having a glorious summer and welcome to the 15 new subscribers,

I'm Dr Eliza Filby, a historian of generations who explores how society is changing through the prism of age. In this fortnightly newsletter to you will find articles written by me as well as insights, links and news on generational shifts in the workplace, consumption and society at large. Helping you feel out of touch and up-to-date in equal measure!

In this week's edition:

Exclusive Article: The Privilege that Defines Us

Me in the Financial Times on Gen Z

When are humans at their happiest? (clue: it's not your twenties)

Why reading the news is the new smoking

How Gen Z searches for stuff

What A Privilege: How the Inheritance Economy is Shaping our Future

It is hard for any of us to think in terms of billions, let alone trillions, but that is what we are talking about when it comes to the sums around family inheritance. Over the next 30 years, in the UK, approximately £5.5 trillion of family wealth will be transferred down the generations. In the US, the reported figure ranges from $30-$68 trillion. It is the largest transference of wealth in human history.

There was a time, not that long ago, when inheritance, and all the considerations that come with it, was the preserve of the aristocracy. So much so that it formed the narrative backbone of most 19th century novels. And yet in the 21st century, inheritance has become democratised; shaping family finances across the class system. As a result, it has also become a leading thread in this century’s story of rising social inequality, intergenerational unfairness, the property and asset bubble, delayed adulthood and dependency culture within the family.

Whether we realise it or not, we are living in the inheritance economy where, if you are under 40, your life’s chances and opportunities are to a large extent determined by what you are set to inherit rather than what you learn or earn. Familial financial support is the defining millennial privilege and the dividing line shaping our past, present and future.

So how did we get here? Over 70% of household wealth in the UK is held by the over-50s. In the US the statistic is roughly the same. We know that wealth and assets dominate the economy and that these are uniquely held by older generations. As we are all beginning to appreciate, this was not simply because that generation worked exceptionally hard but because they were the benefactors of exceptional social, economic and political conditions unlikely ever to be repeated (sorry millennials). The post-war combination of good wages, generous pensions and affordable homes has resulted in the accumulation of wealth in the hands of one demographic across the western world. And there is a decidedly racial element in this intergenerational unfairness; black millennials in the US, for example, own 52% less wealth than Black Baby Boomers had generated by their age.

To put it crudely, the circumstances of a meritocratic society have over time given rise to a form of generational plutocracy. In the UK, this wealth has not been ‘earned’ as such, for 70% of it is tied up in property whose value reflects the UK’s short supply rather than owner investment. Forget blaming Thatcher or Reagan, the right or wrongs of this evolution are now largely irrelevant. The important fact is that this generation is dying out and the wealth is on the move.

Where it goes is a question that will directly or indirectly dominate politics for the next twenty years.

In America, it has been estimated that Gen X will inherit 57% of this wealth while millennials will inherit the rest. In reality though, most of it will come too late for either to spend on themselves, and most likely will be passed onto their Generation Z and Generation Alpha kids respectively. Grandparents are already paying 15-20% of private school fees in the UK. The legacy of what the financial services industry calls the Great Wealth Transfer will continue to impact generations to come.

Millennials on average are set to receive 16% of their lifetime household income in the form of inheritance, which is perhaps why nine out of ten people in the UK say they are relying on a lump sum to pay off debts and subsidise their retirement. 66% of millennials in particular are hopeful that an inheritance will fund their lifestyle and provide the financial security that has so far alluded them. Given this reliance, it is little wonder then that one in five millennials worry that their parents are squandering this inheritance through overspending. And that is before the social care receipts come in.

This culture of reliance, or expectation, has its downsides and is already beginning to play out in the law courts. In the UK High Court, inheritance disputes have tripled in the last decade. With the complexities of the modern blended family, with divorces and step-children, this is only set to increase. But as well as the lawyers, it is the legions of financial advisors and wealth managers - those sectors that are built around preserving and growing wealth - who are hoping to reap the rewards. They have been capitalising on the Baby Boomer buck since the 1980s but they may well find their mid-life millennial inheritors more predisposed to play catch up on their spending rather than saving.

Back in the nineties, we still believed that university was the principle driver of opportunity and advancement. I was the first person in my family to get a degree; but this statement gives a complete misreading of my current class, parental support and privilege. For the millennial generation, the distinction is not the launch pad of a degree but the safety net of mum and dad and whether they were canny enough to buy property in the 80s/90s.

We know that the Bank of Mum and Dad is the sixth largest mortgage lender in the UK; what is less calculable is the aggregate effect of parental support that affluent millennials were able to tap into as they meandered through early adulthood. There are many who had the luxury of having their inheritance drip fed to them throughout their twenties and thirties, helping them prolong adolescence and fast track into adulthood on their own terms.

When millennials were young, we were never naive enough to think that school and university was a level playing field and yet the real division was only truly revealed at early adulthood, often at the point of graduation. The distinction between those who never received letters from the Student Loans Company and those that still get them in their forties, between those who could afford to pursue more qualifications and those who did not have the luxury of trying out different career options, between those who could seamlessly migrate to a city and those who never left their hometown, between those who received a monthly parental direct debit to supplement their low wages and those who only ever had multiple jobs, between those who received a wedge of a deposit for a first flat and those who will never be able to afford a home, between those who had an all-inclusive wedding and nursery fees paid by grandma and those who’ve struggled with the traditional load of adult responsibility.

For these reasons, the inheritance economy is not only responsible for much of our current levels of inequality but will be instrumental in perpetuating it. For the past ten years, the millennial generational identity has crystallised around a compelling narrative of intergenerational unfairness but this solidarity will come unstuck as their parents die out and the wealth trickles down to the lucky ones. What we are facing is a moment where intergenerational warfare will transition into intragenerational class conflict.

And yet, class conflict is not quite the right word here. Because the inheritance economy is also changing the definition of class itself. No longer is your class tied to your professional status or even what you earn. Arguably the most frustrated and stunted group are those graduates with professional well paid jobs who are struggling to maintain the middle class lifestyle with which their job is traditionally associated. Academics being the obvious example. And these are the lucky ones. Those non-graduates with limited access to professional well paid jobs and little inheritance are the target for the UK’s levelling up agenda precisely because they have been forgotten for so long.

Where all this goes politically is the key question. Jeremy Corbyn’s appeal was precisely to that frustrated, urban dwelling graduate professional millennial demographic even though his pledge to raise inheritance tax in his 2019 manifesto was still moderate compared to historical standards in the UK. Few politicians would dare take French economist Thomas Piketty’s line that private property should be temporary and that you shouldn’t be allowed to pass it on when you die. Any government, right or left, pledging a redistributive policy to even out the playing field (either on inheritance tax or capital gains tax in respect to property) runs the serious risk of alienating Boomers who want to help their kids and the more hard-headed millennials who expect to inherit. It will be a tricky balance. The inheritance economy produces a fundamental problem for politicians and arguably democracy itself, where any promises of making life better for the next generation ultimately ring hollow against a system of insurmountable unfairness.

But ultimately, the inheritance economy will prove deeply problematic for us all. For employers who find it hard to motivate their employees through salary alone, for families seeking to navigate this transference as elegantly and pain free as possible in the context of an ageing society, and especially for millennials because we were the generation who were told that if you worked hard and were martyrs to the philosophy of self improvement and self actualisation, then you could achieve anything. The truth is that our fate was always tied to our parents’ purse. It’s trickle down economics but not as we know it, and the consequences will be profound.

Reasons to be cheerful from Noah Smith

Recommended Links....

1. How the internet ruined homework - it will not surprise you.

2. The Gen Z historian on TikTok - hidden histories and debunking myths to his 500k followers. One great example of how TT is developing into a platform beyond make up transformations and dance crazes.

3. Why Reading the News is the New Smoking A valid argument, it was hard to not disagree with any of this.

4. For Millennials, finally some good news: The age of 'established adulthood', the career and care juggle when you have kids, buy a house, settle down is actually, according to this research, the point when human beings are at their happiest. Major caveat: the researchers predominantly surveyed white affluent Americans.....

People to Follow....

Adrienne: Social Media Strategist. Excellent video on why 40% of Gen Z are now using TikTok for search rather than Google...because they don't want or need to do as much searching. Feels alien to this geriatric millennial and a scary stat for Google.

Feast for the Senses....

1. READING: Megan Gerhardt's thought-provoking Gentelligence book on why ageism is so pervasive and how we can fix it in the workplace.

2. LISTENING: To the rain (mostly on YouTube) an easy way to trick your mind and body into thinking it's cool in a heatwave.

3. WATCHING: Trainwreck: WoodStock '99 a scary reminder of Gen X Jackass masculinity of the '90s and some of the appalling music of that decade.

4. VISITING: I could do a whole newsletter on family friendly activities in Devon but I won't.

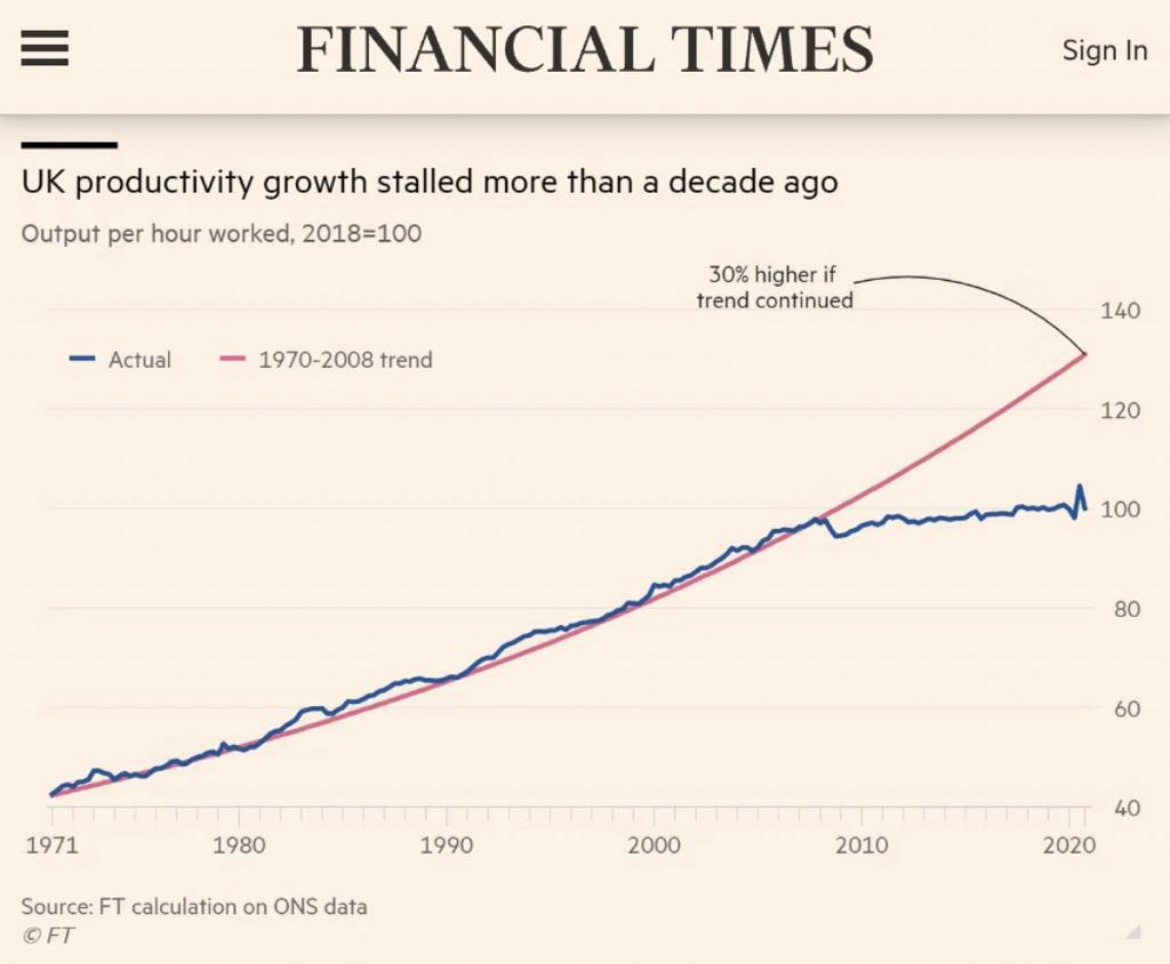

and FINALLY, UK productivity dropped in 2010 - coincidentally the year when smartphones began to outsell PCs.